According to Jewish law, a divorce must be given by the husband’s free will. Occasionally the husband holds the “get”, or Jewish divorce decree over his wife’s head in order to obtain a better custody or property arrangement, or to punish her. This leads to situations in which a wife has obtained a civil divorce, but cannot remarry under Jewish law. This also has implications for any future children she might have.

One session of the Tahel conference on abuse in the religious community, on December 1 in Jerusalem, entitled “Get Laws around the World,” dealt with attempts to resolve these issues from within the legal system.

The attorneys on the panel all specialize in matrimonial law, and practice within the Jewish community. They emphasized the importance of educating members of their profession, who may be unaware of how the law can help their clients obtain a get.

Two main methods within the legal system are used to ensure that a get is given or received. First, some countries or localities make the giving/receiving of a get a requirement for finalizing a divorce, or to achieve a ruling on financial or custody arrangements. Second, in some countries refusal to give or receive a get might be considered a form of domestic abuse. Get refusal thus becomes subject to criminal law.

Another issue faced by all of the attorneys are the batei din (religious courts) who claim that strong laws constitute coercion, and make a subsequent get invalid. Attorney Sharon Shore of Toronto pointed out that it depends on who is doing the coercion. The beit din will give more leeway to coercion from the Jewish community, than from the secular court system.

Att. Esther Schonfeld

Att. Aliza Goldring

United States

Esther Schonfeld, partner at the New York matrimonial law firm of Schonfeld and Goldring, spoke first. New York State leads the U.S. in awareness of the get crisis. The first get law (Section 253), passed in 1983, denies civil divorce to anyone who puts up barriers to the spouse’s remarriage. It only applied to the plaintiff.

In 1992, the New York state laws were amended to allow equitable property distribution following a divorce. It included a clause stipulating that if either side puts up a barrier to the other partner’s remarriage, including a religious one, they risked losing their share.

According to Schonfeld, “We deal with this on a daily basis. In Kings County (Brooklyn), the law has been applied in many decisions. In the last three decades that the get law has been on the books, it has nudged hundreds of men and women to go through the religious divorce process.”

Schonfeld’s partner, Aliza Goldring, spoke about the success of the get law in settling cases before or during litigation, by taking away control that the husband wielded with the get. The marital estate, which might include retirement accounts, a family business, or a home, are usually divided fifty-fifty. Not only can the husband not withhold the get to pressure the wife to give up the property, should he not remove barriers to her remarriage, he won’t get anything. In one case, the wife got all of the property including a house in Flatbush worth several million dollars, because the husband had not granted a get.

Sometimes attorneys in Goldring’s firm explain the legal ramifications of the get law to the husband’s attorney, who may be able to convince his client to grant the get.

Att. Rachel Marks

Rachel Marks, an attorney in the same firm, brought up three types of cases where the legal system can’t help, or “Why there are still agunot (chained wives, unable to remarry under Jewish law) in New York.”

- Lack of knowledge. The get law only works if it is invoked. Her firm gets frequent calls from colleagues asking them to explain the law and its implications.

- Money. If the couple doesn’t have many financial assets, or if there has been a financial prenuptial agreement and a short marriage, there is not much property to divide. So invoking the law will not be effective. Sometimes the husband has assets, but doesn’t care. These are often abusive situations. In one case, a husband said he would not give his wife a get until she was beyond childbearing years. This woman did eventually get an annulment from reputable beit din and remarried.

- Halachic (Jewish law) concerns. Some rabbis consider a get given because of civil law to be coercion, and therefore invalid. If the court makes a decision to reallocate marital funds because of the lack of a get, they consider it a civil body making a decision about the marriage. Fortunately, many rabbis feel that granting a get as a result of the law is proper usage, and should be applied.

Halachic pre-nuptial agreements work, but not enough couples have signed them. According to Schonfeld, “It amazes us, in light of the get crisis, that so many couples have not signed the pre-nup.” Couples say either that their rabbi told them not to sign, or that “we never thought it would happen to us.” Attorney Martin Friedlander, founder of the new Yashar coalition that launched at the Tahel conference, is working on a new halachic pre-nup that will be more acceptable to the haredi and hasidic communities in New York. Members of Yashar must pledge not to represent clients until they have granted a get.

Canada

Sharon Shore is a partner at Epstein-Kohl in Toronto, Ontario, and a frequent speaker on family law issues.

In 1999 federal and provincial (Ontario) law was changed to state that if someone hasn’t removed religious barriers to their ex-spouse’s remarriage, they will have their claims dismissed or pleadings struck. The law gives the wife the right to go back to court and ask for whatever she wants, as long as she has some evidence for the request. The husband’s only recourse is to claim that there are religious reasons for not giving the get, but no court has yet accepted this claim.

The law is remedial in nature. If the husband gives the get, his pleadings will be reinstated.

The beit din, or religious court, in Toronto doesn’t like this law, and won’t allow the husband to give a get that results from a ruling in the civil court.

Shore says, ” In some cases I’ve settled everything and husband still won’t give the get. In Ontario, if you settle everything but the get, you are negligent. Don’t do anything, but make sure you have the get signed.”

In the case of Bruker v. Marcovitz, the Supreme Court awarded a wife $47,000 because the husband had not granted a get for over 15 years. If the woman had still been of childbearing age, it might have been more.

In a disappointing case, Shore’s client from the Bobov hasidic community was pressured to give up both property and the custody of her children in exchange for the get. She signed the agreement and planned to go to civil court, but the religious court then withdrew her heter (religious dispensation) to go to civil court. By then it was too late for her—she had given up her children and all her money. The lesson learned is not to rely on provisions. You always have to work with the beit din.

Sometimes the husband convinces the beit din that he is giving the get out of free will and not because of the civil court.

The Rabbinical Council of America’s halachic prenuptial agreement does not work in Canada. Because of issues related to sharia law, the law states that you can only go to arbitration with a designated “family arbitrator.” In the U.S., the halachic pre-nup allows the beit din to arbitrate. Shore has the designation, but rabbis cannot do arbitration. The only thing that the beit din can do is mediate or give the get. But there is good news, Shore reports: “With the assistance of Rabbi Whitman and the RCA, a new halachic prenuptial agreement for Canada will hopefully be launched by the end of this year.”

United Kingdom

Att. Deanna Levine, UK

Deanna Levine is a member of the Scottish/English United Kindom’s association of Jewish lawyers. She educates Jewish and general audiences on the get. You can find more information at the website Getting Your Get.

In England and Wales, divorce involves two stages: decree nisi (conditional) and decree absolute. Divorce law refers to “usages of the Jews,” but does not explicitly mention the get. One of the spouses must apply after the decree nisi is granted. If one spouse is not cooperating, the divorce cannot go to its final stage of decree absolute. The recalcitrant spouse tends to cave in when he or she is going to be made responsible for the cost of the application of law.

In the case of Brett v Brett, the judge ordered a recalcitrant husband to pay thousands of pounds, but the amount would be reduced if gave a get. At first the beit din thought it was great, but then the opinion changed and this get was not regarded as “kosher.”

Conditions to give and receive a get are normally included in the consent order, in relation to the decree absolute. Civil divorce is separate from the financial agreement. There are serious consequences if undertakings (legal promises) are not abided by, including fines and prison. This can come into play after the granting of the decree absolute, or at any stage.

But the beit din must be satisfied that the get is given by the husband’s own free will and not because of undertakings.

The Serious Crimes Act 2015 is, according to Levine, “the most amazing piece of legislation yet.” The law is so new that a guide has not been published for prosecutors.

Two provisions deal with psychological or emotional domestic abuse and refer to controlling or coercive behavior that could be relevant to get refusal. The abuser and victim must live together, which is not the case in most cases of get refusal. A high standard of evidence is required. But if the hurdles can be overcome, violators can be subject to a fine or five years of prison.

Australia

Att. Talya Faigenbaum

Talya Faigenbaum of Melbourne recently won an award from the Australian Women in Law group, and has been called the “hasidic Erin Brockovich.”

According to Faigenbaum, the Australian legal system is very conservative, but also trend-setting. In 1975, it overhauled all marriage laws and introduced a no-fault system.

Any ancillary orders arising out the marriage can be applied to the get. A husband and wife can be ordered to cooperate with the Melbourne Beit Din. But in order to avoid issues of coercion, it only requires attendance and not completion of the divorce. The method is uncertain and has financial and emotional costs.

Prenuptial agreements don’t work in Australia, because financial agreements have strict legal requirements. Faigenbaum says they could theoretically put in a get clause, but when you enter into a financial agreement, you abrogate your right to ask for any other claims. A financial agreement can also be very costly and complicated, ranging from AUD 3500 -15,000.

So that leaves us with domestic violence laws, which are very broad and similar to the U.K.’s Serious Crimes Act.

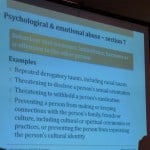

The abusive behavior is not necessarily physical abuse, and is very victim-focused. The consequences are serious. Examples of violations include repeated derogatory taunts, threatening to disclose sexual orientation, withholding medication, and making or keeping connections. Even exclusion from the synagogue could fall under the law.

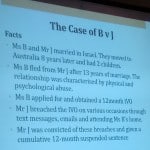

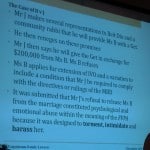

Below are slides that Faigenbaum provided about the legislation and a case in which it was applied to get refusal. The response of the judge was extremely gratifying. In the case of B v. J there was already physical and emotional violence. So it remains to be seen whether get refusal alone would be a breach of the domestic violence law.

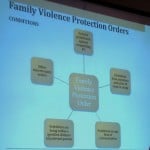

- Family violence order

- Psychological Abuse

- B v. J Slide 1

- B v. J slide 2

- B v. J Slide 3

- Implications for Get Refusal

Keshet Starr

The session was summed up by Attorney Keshet Starr of ORA, which she described as the only non-profit addressing the agunah issue internationally. Starr pointed out that each country’s system has weaknesses. There are also pitfalls to proceeding with limited support from the rabbis.

Starr emphasized the importance of presenting the issue to the legal community in language that they can understand. The language of domestic abuse, and not esoteric halachic terminology, is more effective.

Read Shoshanna Keats-Jaskoll’s post about Yashar and legal solutions to the agunah issue, which appeared in Jerusalem Post’s “In Jerusalem.” I gave her access to my preliminary notes and images, and she credited me at the end.

Related articles:

Joint Custody for Children of Divorce?

I wish Rabbis weren’t so timid. I know it might technically invalidate a Get, but refusers should be reminded that there’s another way to free a woman to remarry.

It’s not PC to beat the husband.

Don’t you know that in this world, PC is all that counts?

– It’s not PC to say daycare is bad for kids.

– It’s not PC to say that being homo can make you terminally ill.

– It’s not PC to say that Israel is the victim and Muslims are the perps.

– It’s not PC to say that if there was an option to have the husband earn double income and the wife stay home, a lot of society’s problems would be solved.

– It’s not PC to say that not everyone needs to learn in college, and that not everyone *can* learn in college.

– It’s not PC to say that there are some people who are simply not as intelligent as others.

– It’s not PC to say that gifted kids suffer in the school system.

– It’s not PC to say that baby formula is a medicine that should only be given when medically necessary…..just like any other medicine

– It’s not PC to say that teachers are overworked and underpaid (because so is everyone else, don’t you know?) and that teachers’ vacation days are not the root of all evil.

– It’s not PC to say that non-vaccinators are putting the rest of our kids at risk.

– It’s not PC to say that maybe, maybe, there are women out there who abuse their husbands and then claim to be abused *by* their husbands.

Want more?

So yeah. It would be nice if the beit din would beat the husband, but as long as we are slaves to being PC, that ain’t gonna happen. Nothing to do with halacha.

Thank you for this very interesting and important article!

I saw an almost identical one by Ms. Jaskoll– was that intentional?

Also, the Canadian case was Bruker v. Marcovitz, the UK case is Brett v Brett, and the law is the Serious Crime Act 2015. It would be worthwhile to double check the titles and citations with a quick google search, or maybe even read some of the original cases and legislations inside. They’re very interesting and accessible and the details are important! Thanks again.

Shoshana Keats Jaskoll used my preliminary notes for her article, and credited me at the end.

Thank you for the corrections. I will fix the errors.